My guest post for The Foreigner:

Today’s headlines are dominated by Iran after a plot to kill the Saudi ambassador to the U.S. was revealed yesterday. Open conflict among the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and Iran may not be imminent, but conflict within Iran is ongoing, as conservative factions struggle to form a unified camp and President Ahmadinejad’s party is marginalized even further.

Iran’s maverick president has caused so much acrimony since his disputed re-election in 2009 that the conservatives are more fractured than ever. This fragmentation not only presents obstacles to running the country, but also poses problems for the conservatives as parliamentary elections approach in March 2012.

As the conservatives gear up for the upcoming polls, coalitions and alliances are proving to be more difficult to form than ever. One reason for this was the recent fierce battle between Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and Ahmadinejad, which alienated some of the newcomers to the conservative camp. For example, Ahmadinejad’s Chief of Staff, Esfandiar Rahim Mashaiee and his supporters were labeled as the “deviant movement” for their unorthodox, and by some standards heretical, views of Shiite theology. Conservative camps had to choose a side. They were either with the Supreme Leader, or with their nonconformist president.

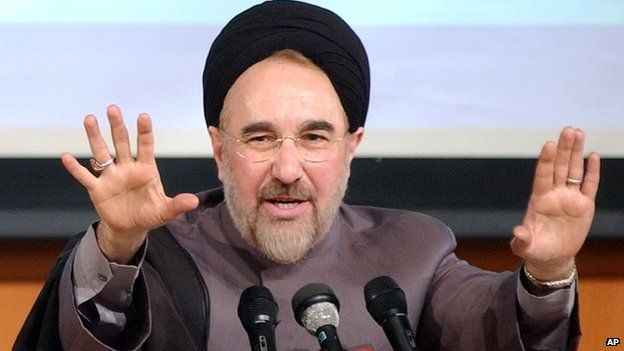

Partisan infighting is not a new phenomenon. The 32-year history of the Islamic Republic consists of complicated and nuanced internal strife between the country’s numerous political factions. Evidently, the reformist years of President Khatami, 1997-2005, and the events following the disputed 2009 presidential election highlighted the distinctions between the reformist and conservative factions of the regime. However, misguidedly, the country’s ruling conservative faction is often painted as a monolithic and unified force. In fact, there are numerous shades of conservatism in Iran, which frequently cause disputes among the ruling clerics.

Case in point was the reaction of the conservatives to the results of the contested 2009 presidential elections. More traditional conservatives, such as Mohsen Rezaei, influential politician and former Revolutionary Guard Commander, went as far as to question the election result, while more radical individuals, such as Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, hardliner cleric and a member of the Assembly of Experts, decidedly announced their support for the re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Conservative rifts will not have an immediate impact on Iran’s nuclear policy or the country’s general attitude toward the United States. The diversity among the conservatives is related to their ideological and domestic policy differences. As for Iran’s nuclear program, the extreme majority of the conservatives agree with the country’s right to pursue its nuclear ambitions. This is a domestic battle and the winner will attempt to impose his own version of conservatism while in power.

In preparation for the upcoming elections, Iran’s conservative forces have started an inner- party dialogue, which is often backed by public statements indicative of their progress. The conservative forces consist of traditional factions, neo-conservatives, and right-leaning groups.

The Traditional Groups

- Combatant Clergy Association, Jame’e-ye Rowhaniyat-e Mobarez, founded in 1978, plays an important role in deciding the conservative political agenda in the country. The positions by the group tend to be aligned with the government and based on the traditional conservative line of thinking. Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani, Chairman of the Assembly of Experts and the head of Combatant Clergy Association, has expressed concern about the divisions in the conservative camp, and he is attempting to act as an appeasing force among the different factions.

- Society of the Lecturers of Qom Seminary, Jame’eh-ye Modarresin-e Howzeh-ye Elmiyyeh Qom, founded in 1961, is a conservative group that nominates the lecturers of the Qom seminary who are aligned with the regime. The society is headed by Mohammad Yazdi, Iran’s former Head of Judiciary. More than likely, this group will play the role of an appeaser in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

- The Islamic Coalition Party, Hezb-e Motalefeh-ye Eslami, founded in 1962, is traditionally close to Iran’s bazaari merchants. They helped in funding the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to Iran during the 1979 Revolution. They are one of the most powerful and influential conservative coalitions and have strong connections with the non-governmental financial institutions. They tend to lean toward moderate conservatism.

- The Followers of Imam’s Line and the Supreme Leader, Jebhe-ye Peyrovan Khat-e Emam va Rahbari, is a coalition of 14 conservative political groups. Habibollah Asgaroladi is the chairman of this coalition and they tend to function under the umbrella of the the Hezb-e Motalefeh-ye Eslami.

Iranian New Conservatives

The participation of three influential figures who comprise the new conservative camp is important to note; Ali Larijani, Chairman of the Parliament, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, Mayor of Tehran, and Mohsen Rezaie, former IRGC commander and a member of the Expediency Council.

It is difficult to gauge the involvement of these individuals in the upcoming parliamentary elections, but more than likely they will act as influential figures who will set forth the agenda of the conservative party as a whole. The trio does not represent new figures in the Iranian political scene, but their emphasis on liberal economic policies, moderate political ideology, and criticism toward the radical factions has earned them the title of the “new conservatives” in Iran.

Ali Larijani is not part of an official conservative group, but he and his brothers hold key political positions in the system. He is the parliamentary member from Qom, which has made his relationship with the ruling clergy more significant and more influential.As the mayor of the capital, Ghalibaf has proven to be a capable technocrat, managing one of the largest urban areas in the world. He tends to stay away from any political infighting and often uses his newspaper—the Tehran Emrooz—to broadcast his opinions.

Mohsen Rezaie founded the Resistance Front, Jebheye Istadegi, after the 2009 presidential elections in order to analyze the issues facing the conservatives. He is a regular commentator on various media outlets.

The Radical Right

- Esfandiar Rahim Mashaiee, president Ahmadinejad’s closest confidant and his in-law, is the main organizer of support for the president and his faction in the parliament. After the political battle between Ahmadinejad and Khamenei, this group has an uncertain future. It is not clear if they will have enough political influence to carry on.

- Society of the Devotees of the Islamic Republic, Jam`iyat-e Isargaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, informally referred to as Isargaran,is a radical right-wing group, which was originally founded by Ahmadinejad. After the president’s scuffle with the Supreme Leader, Ahmadinejad’s name has been removed from the society’s executive board.The group has focused on highlighting the economic class differences existing in Iranian society. They pander to the impoverished individuals in the public and have been claiming to pursue “justice, simple living, and combating economic corruption.” The executive board consists of 16 individuals, headed by Hossein Fadaie.

- Unwavering Front, Jebheye Paydar, headed by the conservative cleric, Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi. This coalition has entered the arena to serve as the alliance against candidates supporting Mashaiee. This group does not believe in the political philosophy of the more moderate factions, such as the Combatant Clergy Association and Society of the Lectures of Qom Seminary, and individuals such as Mahdavi Kani.This group has distanced itself from the “deviant movement,” but it still supports Ahmadinejad. It is attempting to make a distinction from the Mashaiee camp and the president.

At a cursory glance the Iranian conservative block might appear to be a unified and cohesive body, but in reality it consists of a number of diverse factions and individuals with different beliefs. Although the internal political struggle does not have an immediate impact on Iran’s posture toward the United States, it has major implications for the future stability and nature of the regime. Understanding the differences between the various conservative groups in Iran can help us form a more complete picture of the ambiguous decision-making process in Iran.